Final generation for printed text?

November 16, 2021

Since its birth in 868 AD, the printed book has revolutionized the world of education and learning, providing the ability to spread stories, immortalize history, and record information.

However, the invention of virtual reading platforms such as the Kindle, Google Books, and Project Gutenberg have forced the world of literature to consider the possible obsolescence of physical books.

While a world without physical books may seem unfathomable to readers, in recent years the extinction of printed books has transformed from an unthinkable proposition to a very real possibility.

“Right at this point, after COVID, it’s really really hard to tell because students have to do so much online. We are beginning to see more students coming in (to the library) but mostly to study, not so much for books. My personal feeling is I don’t want to see books go away because I like to have the physical version,” said Mimi, who works at Oakton’s library circulation desk.

Despite the sentimental and aesthetic value of traditional books, the reasons for trading in paper books for their contemporary counterparts are plentiful. For example, college students can now purchase or download textbooks for a fraction of the cost of traditional textbooks. According to the BBC, online/animated books aid vocabulary comprehension in young children, as well as may give developing countries the ability to become literate.

When this evidence is presented, the argumentative scales begin to tip towards the direction of book obsolescence– with so much convenience, what could go wrong?

It turns out, a lot. The looming death of the era of paper books has faced a mob of controversy and critics.

For instance, there is concern that reading online will actually alter the manner in which readers think. According to Maryanne Wolf, director of the Center for Reading and Language Research at Tufts University in Massachusetts, and author of Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain, online reading will result in ‘short-circuit’ minds, in turn damaging critical thinking skills, analytical abilities, long-term focus, and story comprehension.

“I find myself distracted with e-books, because the tech is right at your fingertips so it’s too easy to get distracted by other apps and notifications and such,” said Oakton student Danielle De La Rosa. “I do worry about the future of physical books since everything is so technology-centered now and people’s attention spans are getting shorter because of it.”

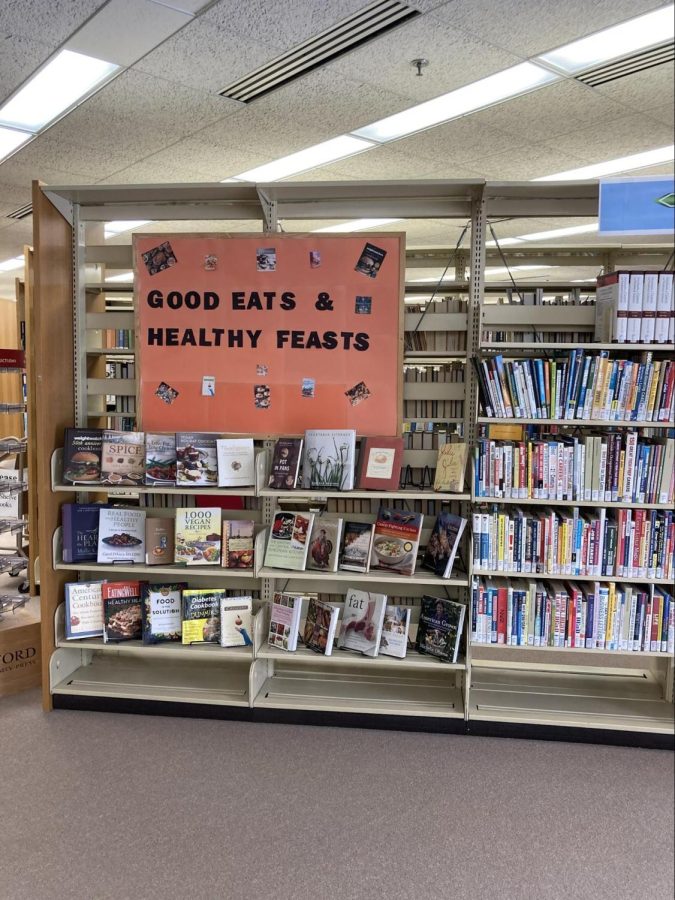

This sudden change in book popularity has slashed library budgets and caused the closure of certain branches. In an effort to grapple with the sudden decline of readers, libraries have scrambled to remain relevant.

Libraries are no longer limited to silent reading and revision; now, libraries have evolved into media centers, digital resource centers, and places for students to gather and collaborate.

Textbook manufacturers have also been negatively impacted; in fact, a study on the sales of CampusBooks Inc. has shown that textbook book prices have decreased 26 percent since 2017 due to reduced demand. Furthermore, according to the same study done with CampusBooks Inc., the market for virtual books has expanded by 95 percent in light of increased online variety and availability.

There is also the argument of aesthetics and gravitas. It is almost incomprehensible to argue that touching a physical book, feeling the smoothness of the cover and break of the spine and the creak of the hinge, will ever compare to holding an iPad or Kindle. “I think we’ve all read Fahrenheit 451 for English class, and that’s about how I think it will go… maybe not as dramatic, but similarly,” said Oakton student Ellie Martin.

Despite the dismay of educators, librarians, and linguists alike, the general consensus seems to be that books will ultimately become obsolete. It is only logical to assume that lighter, customizable, and more compact forms of literature will be favored over their bulkier counterparts; if most of the developed world is headed in the trajectory of modernization, why wouldn’t books follow?

Fear not, readers, classicists, and traditional book-lovers: such a day will likely not arrive for another 50-100 years. “They will remain, but they will be in the minority,” said Mimi.

The great expanse of educational future stretches out before us, and while many of the details of the world’s rapidly developing society are blurred, one thing is certain: time ticks steadily on, whether or not we are in agreement with its measured march.